|

Doug Cummings and Trond Trondsen / robert-bresson.comA Man Escaped [Un condamné à mort s'est échappé, 1956 ]Region 1 DVD: New Yorker Video, 2004

THE FILM

"I had quite a lot on my side: an increasingly determined urge to escape, a plan already sketched out in broad outline and partially realized, the stupidity of the Germans, and a certain congenital predisposition to good luck on which I was always consciously drawn. There were two elements in this plan: mine and God's. Where, I wondered, was the dividing-line set? But the film is far from a religious tract. When René Guyonnet of L'Express asked Bresson if one could find "extraordinary praise for the perseverance of faith" in the film, he replied, "This praise is not the subject, but follows from the subject." When asked about the film's sense of mysticism, he elaborated: "I do not believe that everything in a film is put there. You include some things without including them. What you call my 'mysticism' must derive from this. In Un Condamné I tried to make the audience feel these extraordinary currents which existed in the German prisons during the Resistance, the presence of something or someone unseen; a hand that directs all." If Bresson seems to be editorializing his source material, he can be forgiven, as one of the few widely-known biographical details of his life is that he spent 16 months as a German prisoner-of-war himself, from March of 1940 to June of 1941. The intensity and realism of the film's visual and aural detail surely owes a great deal to this experience. In addition, the film's tension between free will and determinism was a quintessential theme of postwar France exemplified by the existentialist writings of Jean-Paul Sartre, Jean Anouilh, and Albert Camus, who was a friend of Bresson's. Questions of political occupation and personal responsibility, individual choice and fate were of paramount importance in a country processing its recent historical travails. As Allen Thither writes in The Cinematic Muse: Critical Studies in the History of French Cinema (1979):

"It is, in fact, with a Kierkegaardian understanding of religious paradox that one must begin an interpretation of Un condamné à mort, for in one sense this is a film about an unmediated relationship between the particular and the absolute. The cultural context that grounds the narrative project is, in general terms, that system of existentialist religious values in which the oppositions of faith and despair, freedom and grace, or spirit and flesh establish a coherent semantic field." Bresson ingeniously conveys these philosophical themes through concrete and material means. In the opening scene of the film, Lieutenant Fontaine, the film's protagonist (played by François Leterrier, a local philosophy student), is being transported to Montluc in the back of a car, seated beside two handcuffed prisoners. Bresson creates suspense as Fontaine eyes the road and fingers his door handle. Just when a tram passes before the car and it stops, Fontaine flings open his door and leaps to freedom. But Bresson's camera, like the other prisoners, stares immutably ahead without panning with the action. Offscreen gunshots echo and figures are seen running outside the vehicle. The camera remains motionless. Within moments, Fontaine is apprehended and brought back to the car, restoring the frame's composition, where he is handcuffed and cruelly beaten. In this first scene, Bresson establishes the tension between blind chance and inescapable fate. A Man Escaped was the filmmaker's first film with an entirely non-professional cast and it crystallized his mature aesthetic: a shallow depth of field in the compositions, automatic and barely-emotive performances, a heavy dependence on sound effects--particularly those occurring offscreen, isolated instances of music, brief dialogue, and elliptical editing that omits narrative detail in order to provoke mystery or avoid sensationalism.

The film famously restricts itself to Fontaine's immediate space throughout. The sense of claustrophobia and lack of omniscient perspective submerges the viewer into Fontaine's world. In a bare, concrete cell with nothing but a bed and a barred window that displays a portion of an empty courtyard, the viewer shares Fontaine's joy at the smallest of discoveries--a pencil or a spoon or a box of clothes. Sound reveals a tremendous amount of information: where the prison is situated, what surrounds it, who is near or far, what they are doing. When Fontaine decides to engineer his escape, beginning by scraping his door with a chiseled spoon, it establishes the central visual motif for the film--Fontaine, specifically his hands, interacting with his material environment, forcing his situation, challenging fate by taking advantage of every vagary of chance.

The film's structure progresses from despair to hope, isolation to community. Fontaine begins alone and slowly develops a network of relationships throughout the prison by tapping on the walls of his cell (the very means of separation become conduits of communication) or speaking from his window to Blanchet (Maurice Beerblock), his unseen neighbor in an adjacent cell who initially refuses to communicate. As Fontaine's escape efforts gain legitimacy, however, Blanchet begins to believe in him. When one escapee fails but gives Fontaine important information for his own plans, Blanchet remarks that the prisoner "had to fail so you could succeed." "It's extraordinary," Fontaine replies. "I'm not teaching you anything," Blanchet retorts, and Fontaine nods, "Yes, you are...what's extraordinary is that you just said it." André Devigny died in February 1999 at the age of 82; by the end of the year, Bresson, too, will have passed away.

Chiseling and scraping, devising and communicating, Fontaine fights against his fate (the French title translates more accurately as One Condemned to Death Has Escaped) and restores hope in those around him. A perfectly realized and quietly burning film, Bresson's fourth feature film is not only one of his greatest artistic achievements, but one of his most popular and accessible films as well. It's an excellent entry point into the work of a master. –D.C. (May 2004) THE DVD

"Bresson is a world master and he should be more available through DVD. We are relatively new in the field of DVD. So far we have put out 30 DVDs, and in 2003 we hope to put out roughly 20 new DVDs. Among them we hope to put out two Bresson titles - A MAN ESCAPED and LANCELOT OF THE LAKE - probably toward the end of 2003. Economics aside, the issue is getting quality material from which to make masters for the DVD releases. We've started this process."Mr. Talbot is considered somewhat of a legend in Bresson circles, having purchased the rights for several Bresson films in early 1970s, and then pulling off the incredible feat of arranging to have them screened at several repertory houses in New York City (including Talbot's own New Yorker Theater, the Carnegie Hall and Bleecker Street Cinemas, the Cinema Village, the Elgin, and the Thalia) at a time when financing a theatrical run for such films in New York City was a daunting task indeed. So, with Mr. Talbot's personal promise that the search was on for quality material we settled back for a patient wait. Fast-forward to May of 2004. Has it been worth the wait? Look at the eight screengrabs below (click for larger versions). This is clearly the best we have ever seen the film presented on any consumer video format. The aspect ratio is correct and images look pleasant, with well-balanced contrast. The source elements that were used for this DVD have their fair share of dust, dirt, scratches —and the occasional more serious blemish— but this is totally forgivable; after all, New Yorker never claimed to have done a full restoration. In truth, artifacts having to do with the film elements themselves do not in general bother us as much as artifacts having to do with the film transfer and the digital nature of the DVD medium.

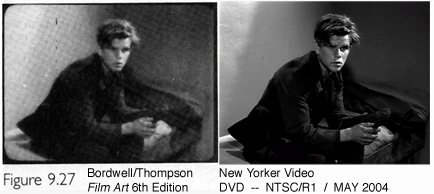

The disc exhibits some cropping, as shown in the following panel which is a comparison between a frame enlargement

found in Bordwell and Thompson's Film Art (6th ed.) on the left, and the corresponding (underscanned) frame as captured from the New Yorker DVD on the right.

When adding the average TV's overscan to the New Yorker disc's cropping, the

end result is, unfortunately, a significantly tighter image than what is seen in the Bordwell & Thompson figure.

The DVD includes a trailer (oddly enough described as a "Foreign Trailer" when it is in actual fact French) as its only bonus material. Subtitles are excellent: they are removable and white, as opposed to those of many earlier New Yorker releases—we like to think that Mortimer Wilson is being listened to (cf. his Commandments #4 and #6).

In conclusion, we are very pleased to see Man Escaped finally out on DVD,

after having suffered through the VHS for all these years. The underlying images are brilliant, but we

are quite frankly both surprised and disappointed that our friends at New Yorker submit to Bressonians a

disc sourced from PAL (with ghosting hard-coded onto the disc, forever ruining individual film frames) rather

than the promised "quality material." New Yorker politely declined our request for comment.

The same PAL source used by New Yorker will undoubtedly make an excellent, crisp (albeit cropped) PAL disc some day.

Unless you are too impatient, or simply unable to play Region 2/PAL DVDs, we recommend waiting for this upcoming disc

— keep an eye on the Masters of Cinema DVD Release Calendar. But by all means, buy several copies

of the New Yorker disc, and hand them out to family and friends (who don't know the first thing about

DVD regions and TV standards anyway). The more people who get to see this truly wonderful film, the better. –T.T. (May 18, 2004)

|