|

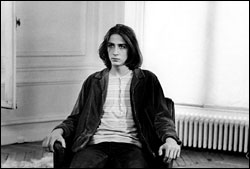

Richard HellThe Devil, Probably

The following is the text of a talk on Robert Bresson given

by Richard Hell preceding a screening of The Devil, Probably

on November 9, 2002 at the YWCA Cine-Club, NYC.

It is reproduced by robert-bresson.com with the kind

permission of the author, who retains copyright.

This article was

first published on the author's own website, richardhell.com.

Photo credit: Anthology Film Archives.

Note that opinions expressed herein are those of the author

and do not necessarily represent the views of

robert-bresson.com/mastersofcinema.org personnel.

But what I was really thinking when I said there's not enough time was that when I consider how I'd like to speak of Robert Bresson, there's not enough time to sort it out. I don't have enough time to be brief! Because it's true I'm not who I was when I was 20 or 25 and I have come to the kind of existence where there's not enough time and I am ultimately glad of that, even if it brings an awareness that I can't do justice to Robert Bresson. But what brings me to this movie this afternoon is the recognition in it of that kid who I was in the 1970's. Doubtless it's presumptuous and ignorant for me to come to the movie in such a self-centered way, but I think it's no worse than coming to it by way of picking pockets. It's a strange path I have had to take to come to Bresson. So I want to talk a little about how this particular movie affected and affects me. As I say, I came to Bresson late. I don't know why. I've always loved movies and I thought I had fairly sophisticated taste and knowledge. It's true that Bresson goes against everything we're conditioned to appreciate in movies by Hollywood and modern life, but then so does Godard whom I've loved since I first saw his movies in my teens. But then Godard did start out riffing on his love for Hollywood genre movies, so he did kind of take you on this educational ride, whereas Bresson is astonishing for his utterly uncompromising fidelity to filmic values that forego all audience manipulation, all pandering for any cheap thrills. For instance, as Susan Sontag pointed out, there's no conventional suspense in his movies. His movie about a prisoner trying to get away actually reveals its denouement in it's title: [Un condamné à mort s'est échappé] [literal translation:] A Man Condemned to Death Escapes ([English release title:] A Man Escaped). In fact it's funny, when we posted at my website in advance of this screening a little account of the story of The Devil, Probably I took the trouble to make the ending of it into a hyperlink that the reader would have to choose so that I wouldn't be giving away the ending unless the reader wanted to know. But of course later when I was looking at the movie again I saw that practically the first shot of the movie is a newspaper headline shouting out the movie's ending. Also there's no humor in Bresson. Well, it is pretty much impossible for anything really good not to be a little funny, but there's as little humor as you can imagine. Dostoevsky seems to have been an artistic brother for him, at least in terms of themes—Pickpocket and Une Femme Douce and Four Nights of a Dreamer are all derived to degrees from Dostoevsky—and maybe the incidental humor in Bresson happens the way it does in Dostoevsky, rooted in grotesque pathos. Nobody ever even smiles in a Bresson movie. I didn't do an absolutely thorough examination, but the only moment I noticed in The Devil Probably where there was a hint of upturned lips on a character was during the most disturbing scene of the movie and happened when the main character Charles realizes the bus he's on is out of control. I also detected exactly one joke. When Charles is in a psychiatrist's office—where he's gone at the insistence of his girlfriend who's worried about his suicidal tendencies—he relates a dream of being dead but of still being hit and trampled by his killers, and the shrink, who looks like a rabid raccoon, asks him, "Do you see yourself as being a martyr [pronounced in French: uh mar-teer]?" And Charles replies, "Only an amateur [ama TER]... When I wanted to drown myself or pull the trigger, I realized it wasn't all that easy." Pun! It's also kind of funny that later on in that psychiatrist scene when Charles in his endearingly sincere way describes again his problem with actually being able to carry out the deed (of suicide) the psychiatrist—in what doesn't seem like some kind of reverse-psychology but actually just out of fatuous self-important pride-in-erudition—points out "That's why the ancient Romans entrusted a servant or friend with the task." Which of course is exactly what Charles needs to hear, as the movie moves to a close... Nearly all movies made are not only essentially filmed theater, but are confections entirely intended to elicit audience saliva, to give them reflexive thrills, to play to their weaknesses. They're fast food and candy. I'm not saying I don't like such movies: there are lots of them that not only give me pleasure but that I respect. For instance in the midst of my thinking about Bresson in the last couple of weeks, I was invited to a screening of a movie by Doris Wishman. She was a woman who made soft-core porn movies, mostly in the '60s and '70s though the one I saw was from the '80s. It was called Let Me Die a Woman and was a "shockumentary" type sexploitation flick about transexuality and it was completely fantastic—and I don't mean that from any kind of so-called irony or double-standard—and it was great to see while I was thinking so strenuously about Bresson because it was for all practical purposes as satisfying as him, as different as its origins were. It was a great demonstration and reminder that good will and a purity of spirit even when fully devoted to the pleasing of an audience can result in a very great movie. [Mention Hitchcock...?] (Though I don't hesitate to say I hate Steven Spielberg, I hate David Fincher.) But Bresson is in a class of his own—the film lover's filmmaker and the filmmaker's filmmaker—for his heroic insistence on fidelity to the soul and truth of film as moving pictures in sequence with sound, rather than mere filmed theater (Filmed theater being acting—people adopting facial expressions as signals of emotions—for instance. But beyond that even, Bresson doesn't want a piece of film to have any significance apart from its relationship with another piece of film. He really means that and it's radical—if you isolate a shot of his there's hardly ever any narrative information in it, if he has to tell you something happened for narrative purposes he's likely just to have someone in the film say it happened.). Doubtless this is partly why it took me so long to find him: his films at first glance and in comparison to what we're barraged with in the way of audio-video can seem straight and colorless and impossibly elliptical. There are no special effects; in fact he uses only one lens even (a fifty millimeter, the single lens that most closely approximates the view of the human eye); he uses music only very sparingly, and by the last few films (such as the one we're seeing today) didn't use any music that didn't originate in the action on screen; and most notoriously he never uses actors, but instead non-actors that he refers to as models, none of whom he ever used more than once, and whom he rehearsed relentlessly to get all taint of expression out of their speech and faces. In fact he tends not to show any extreme moments, anything "dramatic" at all (for instance the way he handles the bus crash scene I referred to, which is partly what's so disturbing about it). He leaves out precisely everything that Hollywood builds movies around. He likes to shoot people's feet, he likes hands on doorknobs, he likes windows and doorways and street noises. Above all it seems to me his movies are like life. Not very much happens in life. But in life, as in Bresson's movies that not very much that is happening is very important, in fact it's God, and after you watch Bresson for a while it's almost unbearably charged and beautiful. Speaking of God, you have to when talking about Bresson. His movies feel spiritual, in the least cornball way possible. My personal definition of God is "the way things are" and that's what it seems to me Bresson's movies are about, as is just about all interesting art one way or another. But once you start learning about Bresson, you discover that he's a Catholic and much is made of his beliefs in that line. Of course most French people are Catholics and it's said that once they get you for your first few years they have you forever. Rimbaud used to write "God is shit" on park benches. Truffaut saw Hitchcock as a Catholic filmmaker. But apparently for at least a significant part of his life Bresson was what is called a Jansenist. I know hardly anything about Catholicism though I've been doing a little research. There are two things I've found mentioned most often about Jansenism. One is the belief that all of life is predestined, and the other is that it's possible to achieve grace but the attainment of it, the gift of it, is gratuitous—grace doesn't necessarily go to the so-called "good." Personally, as perverse as Catholicism has always seemed to me, at this stage of my life I don't find those beliefs strange at all. Naturally Bresson resisted being classed as a Catholic artist in a way that pretended to explain his movies. There's an interview with Paul Schrader where Bresson gets very impatient with Calvinist Schrader's presumptions about him. But Bresson doesn't make a secret of his belief that life is made of predestination and chance. At first glance to many this will seem impossibly strange, but I think it can also be seen as something simple and clear and ordinary, namely a kind of humility and mercy, a kind of forgiveness and compassion, and also as even obviously true. Look at history. Has all the talk, or rather all the doctrine, changed anything? No, people are who they are and things happen as they must. It's nobody's fault and it doesn't change. It's nobody's fault. It's God. Or the devil, probably. It's just how things are. Another quick thing about religion and about Bresson's uncompromising casting of his movies. I think it's interesting that even though Bresson utterly opposes false Hollywood values, his "models" are really good looking. When I first considered this, my reasoning went, a little pettily, ah-ha—so he isn't perfectly pure—he still can't resist attractive people as his "stars" even if they aren't pre-established-commercial-draw type stars; and then, but that's not necessarily "corrupt" in any way—he naturally wants the people who inhabit his stories to be people we care to look at; and then finally I came to the sense that what his models' appearances have in common is the same quality of the models used in medieval and renaissance religious paintings, paintings of saints and martyrs—the faces are hardly ever merely beautiful, the insipid beauty of the fashion model or porn-star type, they're oddly beautiful, they're emphatically but eccentrically beautiful (like Dominique Sanda--of Un Femme Douce--and Anne Wiazemsky, costar of Au hasard, Balthazar), but above all they feel soulful, they read as having an inner life, a depth, even when inhabiting the most deprived of characters like Mouchette. [Sidebar: Many of the leads in his movies—there were thirteen features and Devil was the 12th—never worked in any other films, but Dominique Sanda for Bertolucci [etc.], and Anne Wiazemsky going on to Godard, whom she marries too [etc.], and the odd trivia that Wiazemsky was the granddaughter of Francois Mauriac, and Antoine Monnier who plays Charles in today's movie the great-grandson of Matisse...]. But on to The Devil Probably... I wanted to introduce this particular Bresson movie for very personal reasons. I hope you will bear with me in this. I didn't see this movie until 1999, but it was made in 1977. Bresson's birthdate is half the time listed as 1901 and half the time 1907, so anyway he was at least seventy when he made the film. I was in my twenties in the 1970s and I was writing poems and fiction but mostly writing and playing and recording music, songs. My first album was also released in 1977 and it was called Blank Generation after the song on it of that title. That album and the things I was doing became classed as "punk" along with a lot of other musicians and music that surfaced around then. Frankly though I'd always felt that that album of mine, which I really see as consistent with the other things I was doing at the time including my "novellina" The Voidoid and the book of poems I wrote in collaboration with my then friend Tom Verlaine that we called Wanna Go Out? by Theresa Stern as well as the many interviews I did [not to mention such things as the t-shirt I made which read "please kill me" on the front], were all kind of failed in a significant way, even though they got a considerable amount of attention and even respect. I felt like they were failed because I never got any indication that they were actually received, were "read," were interpreted in the way they were intended. That the overall view of things I was trying to convey, the condition I was trying to express, was never successfully communicated. I didn't really get any indication from the reception my activities got that I was getting through. I remember for instance an interview I did with one of the people who was most sympathetic to what I was doing and saying, Lester Bangs, and I spent the interview trying very hard to elaborate (because he asked me to) on my take on things in songs like "Blank Generation" and "Love Comes in Spurts" and "Who Says (It's Good to be Alive) ?"—songs which he was crazy about, but about which he could only willfully half-hear what I was saying in defense of their message of doubt and hopelessness because he thought there was something immoral in that hopelessness... I tried to explain to him, I wasn't choosing doubt and suspicion and despair, I was taken there by reality. I wasn't affirming it, I was just trying to see clearly. But he couldn't hear that, in my opinion because he was scared of it in himself, but for whatever reason he could only reject my position as being infantile and immoral. And basically he was the only person I was aware of who'd even fully acknowledge these messages that all my work tried to manifest. Everybody else who spoke of it at all just called me solipsistic and nihilist and dismissed it as beneath consideration. And then, after falling in love with Bresson, I come to this particular movie and for the first time find someone, twenty-five years later (when I encountered the movie), but of course independently of any knowledge of me or my local world but in the same period (circa 1977) when I was experiencing these things—and he's perfectly comprehending them and presenting them with the greatest delicacy, respect, and highest artistry. So it wasn't all a dream! How amazing. I existed and Robert Bresson said it matters and is interesting. I not only was but I was worthy of the most careful consideration. To tell you the truth I knew this, but still it is most gratifying to hear it from Bresson. It is so cool to be verified by the filmmaker whom one already loved above all others! So maybe you'll laugh at me, but I'm confident of it and I don't care. I have to admit I have no idea what the significance of the line in the movie that gives it its title is supposed to be. It occurs during that bus scene which I mentioned as being the most disturbing and ominous of the film. I don't know because I have no idea where Bresson is coming from when he brings up "the devil." In the scene, which is full of mirrors and push-buttons and levers and the tops of heads and people's separated midsections, Charles says to his travelling companion, "Governments are shortsighted," and suddenly everybody in the bus is chipping in. One says not to blame governments, "it's the masses who determine events... Obscure forces whose laws are unfathomable." A woman adds, "Yes something is driving us against our will." Someone else: "Yes you have to go along with it," and people continue until someone asks, "So who is it that makes a mockery of humanity? Who's leading us by the nose?" And the first guy who spoke goes, "The devil probably," and the bus crashes and the soundtrack degenerates into horrible honking horns... It's amazing the way everything about the scene builds to a crescendo of ghastliness. There are many such scenes in the film. In fact sometimes looking at the movie I get a feeling of the world as a horrible prison, or some kind of Gnostic-type third rate universe made by degenerate gods. The continuous sharp clicking of the footsteps and the noise of traffic, the evident poisoning of the world by money mad humans, everyone's inability to help each other in any way, the tedious deliberation with which every motion is made... But at the same time it's all breathtakingly beautiful. The movie of Bresson. Though my description of The Devil Probably may make it sound extreme and sensationalistic—what with suicide and predestination and political horrors, etc.—the notable thing really about it and all other Bresson films is its absolute simplicity and its commitment to ordinary moments of everyday life. It's just an everyday life that is lived with open eyes and with a desire to know reality. Bresson was a painter before he made movies and though he described true filmmaking as "writing"—just as he reconceived the people of his films as models, rather than actors, he reconceived cinema as "cinematography," his term used not in the familiar meaning in English of "camera-wielding" (the job of the "camera man" on a movie), but in his own sense of "writing with a motion-picture camera"—along with this, he also referred to himself as a painter all along, with a painter's eyes and sensitivities. (In fact in a late '60s interview with Godard where the origin of Bresson's Au hasard, Balthazar comes up, he says, "The idea came perhaps visually. For I am a painter. The head of a donkey seems to me something admirable. Visual art, no doubt. Then all at once, I believed I saw the film." [Quandt, 1998, p 478]) And Bresson's filmmaking gives a dignity and tremendous power to ordinary life, the truth of life that hardly any other films acknowledge at all. Other films don't trust life or people, they have to give a false drama to everything, make a spectacle of pointless dishonest overstimulation. In Bresson, the quiet becomes excruciatingly rich. I think finally the reason the films have the spiritual feeling they do is precisely because their whole purpose is to try to avoid lying—to try to avoid being misled and to try not to mislead anyone—but rather to just see and listen and reflect. It is such an achievement to notice and consider, it actually becomes way more intense than Star Wars shootouts or whatever.

Believe it or not there is so much more I could say and I

would like to and even intended to say about Bresson, but I

should just let him speak for himself. Let me just point

out that apart from the movies there are two wonderful books

you should get if you are interested in him. The first is

his Notes on Cinematography which is a series of

short notes which more or less encapsulate his intentions

and ideas as a filmmaker; and then this real good recent

anthology of writings about him and interviews with him,

called Robert Bresson edited by James Quandt

(Toronto: Cinemateque Ontario, 1998). The above article is © 2002-2003 Richard Meyers – it may not be reproduced without the express permission of the author. "For myself, there is something which makes suicide possible—not even possible but absolutely necessary: it is the vision of the void, the feeling of void which is impossible to bear." —Bresson [Quandt, 1998, p 489] From The Devil, Probably: Young Man: In losing my life, here's what I'd lose! [He takes out a piece of paper from his pocket and begins to read from it] Family planning. Package holidays, cultural, sporting, linguistic. The cultivated man's library. All sports. How to adopt a child. Parent-Teachers Association. Education. Schooling: 0 to 7 years, 7 to 14 years, 14 to 17 years. Preparation for marriage. Military duties. Europe. Decorations (honorary insignia). The single woman. Sickness: paid. Sickness: unpaid. The successful man. Tax benefits for the elderly. Local rates. Rent-purchase. Radio and television rentals. Credit cards. Home repairs. Index-linking. VAT and the consumer... [He crumples the paper up and throws it with disgust into the fireplace.] Psychiatrist: Loss of appetite often accompanies severe depression. Young Man: I'm not depressed. I just want the right to be myself. Not to be forced to give up wanting more . . . to replace true desires with false ones based on statistics... [The pyschiatrist starts on his diagnosis of the young man's condition.] Psychiatrist: . . . would impede your psychological development and would explain the root of your disgust and your wish to die. Young Man: But I don't want to die! Psychiatrist: Of course you do! Young Man: I hate life. But I hate death, too. I find it appalling. [The young man further contends:] ". . . if I commit suicide . . . I can't think I'll be condemned for not comprehending the incomprehensible."

BIBLIOGRAPHY |