|

Doug Cummings and Trond Trondsen / robert-bresson.comL'ArgentRegion 1: New Yorker, 2005

The Film

Although Bresson had previously adapted several works by Dostoevsky, L'Argent was adapted from a story by Tolstoy, "The Forged Coupon," which depicts the suffering that ensues from the use of a counterfeit check. It was an "account of how evil spreads," said Bresson, whose career had long identified a love of money as a primary human vice—from Michel's "misadventures" in Pickpocket to the heartless miser in Au hasard Balthazar, to the suicide's accomplice in The Devil Probably. And Tolstoy's terse and direct prose seems ready-made for Bresson's physical detail: "After dinner the gymnasium student went back to his room, took the coupon and change from his pocket, and threw it on his desk; then he took off his uniform and put on a jacket. He picked up a worn Latin grammar text for a moment and then got up and locked his door. With a motion of his hand he swept the money off the desk and into a box, took some cigarette papers from the box, filled one with tobacco, rolled it up, and lit it." (trans. David Patterson)Further, Bresson connects the financial swindle (and the subsequent bribes to obscure it) with the idleness and isolation of the middle class; characters seem obsessed with physical beauty (several nude paintings and a scantily clad woman feature in early scenes), an oblivious pedestrian stumbles into a bank robbery while reading his newspaper, and a steady stream of businesspeople and law enforcers perpetually misinterpret events. "[M]y film is about today's unconscious indifference when people only think about themselves and their families," Bresson told Michel Ciment in an interview reprinted in James Quandt's monograph. "But it is not an anti-bourgeois film. It is not about the bourgeoisie, but about specific people. I am a bourgeois myself. I simply happened to have observed people like that. That's what I like about the Tolstoy story. People from other classes can behave in the same way, for the love of their children. They are not intrinsically evil, but their behavior has evil consequences."

Bresson described Yvon as being forsaken by society, and the sense of injustice that pervades the film resides in its contrast between people seemingly protected by an exclusive system and a working class laborer who lacks the social leverage necessary for justice. In jail, Yvon burns with anger as his cellmate blithely tells him, "Someone fond of you protects you from afar. A relative or a friend, say." "I have no relatives, no friends, and no wife," Yvon corrects him. "Never mind," his cellmate answers, "toe the line." Yvon's trajectory in prison is the opposite path taken by Fontaine in A Man Escaped despite the films' similar use of motifs: the rattling of keys, restricted points of view, and an emphasis on penal ritual and the covert ways in which it's subverted (a scene at mass provides the prisoners opportunity to trade contraband). While Fontaine begins the earlier film in solitary confinement and slowly establishes connections with those around him, Yvon is placed in solitary because of tensions with his fellow prisoners and guards and remains emotionally separated from them. Yet in Bresson's paradoxical manner, one of Yvon's greatest defeats is his lack of privacy; everyone, from prison employees to cellmates, intrude upon his personal letters and the details of his crumbling marriage. "Why are they all staring at me?" Yvon protests in the prison cafeteria, and twice in the film he hides his face while grieving, as if to escape the world around him. Like the privileged teenagers, Lucien, the shopkeeper's employee, provides another point of contrast to Yvon. Tasting dishonesty, Lucien becomes a modern day Robin Hood, stealing from the rich and giving to the poor: "I'll be kind when I'm rich," he tells his cohorts, and after he's arrested, insists in court that he's a generous person. (For a director with a reputation for humorlessness, Bresson provides the judge with a wickedly funny response: "The investigation has revealed that, along with your love of good suits.")

L'Argent showcases the filmmaker at the height of his formal ingenuity, particularly his use of narrative ellipses and fragmented space (close-ups of legs, hands, objects). Having already dispensed with nondiegetic music earlier in his career, the entire film provides Bresson an opportunity for artful manipulation of the soundtrack. Passing streetcars, the crackle and jingle of money, the tinny roar of mopeds, the ringing of registers, the screech of sirens and whistles, and prison echoes are all rendered in precise and vivid terms. "In a film," Bresson told Ciment, "sound and picture progress jointly, overtake each other, slip back, come together again, move forward jointly again. What interests me, on a screen, is counterpoint." Bresson's balletic tone could describe an early scene when Yvon is unexpectedly confronted by a waiter. Subdued dining sounds subtly decrescendo as Yvon stands and faces the waiter; a cut suddenly introduces Yvon's fast moving hand as he grabs the man's sweater and pushes him away with a swoosh; the image remains on Yvon's hand—an appendage which has begun its social revolt—while a loud crashing sound is heard offscreen; the image then cuts to the waiter's legs, steadying before a fallen table and broken dishes; after a pause, a car engine if heard slowing down and idling at close range and the image cuts to a police car later in the day. Bresson's counterpoint of sound and image continually emphasizes and intensifies the action. Although the film contains a great deal of formal beauty, it's also an unsparing, severe work that follows its dramatic conflicts to their ultimate end. The bulk of the film's final scenes are set in the idyllic countryside as Yvon contemplates his compulsive desire for violence. The green grass and foliage, rustic sounds of birds and flowing water, and the appearance of one of the few compassionate characters in the film are unexpected relief. Yet the uncommon peace is a "quiet before the storm" (as Bresson described it), and the virtually silent, chilling discovery of an axe in a barn initiates Yvon's final, devastating violence.

The SupplementsNew Yorker Video have utilized the MK2 region 2 release, thus including two short interviews with Bresson around the time of L'Argent's Cannes premiere—one for TV1 with Alain Bévérini and the other with Télévision Suisse Romande—as well as a very brief reflection by Marguerite Duras. In both television interviews, Bresson stresses the spontaneous aspects of his method and the need for surprise and inspiration. Although much of what he says reflects the theories of cinematographic style he expressed elsewhere, it's always a pleasure to see and hear Bresson, one of the cinema's most reclusive artists, still spry and passionate about his work even at an advanced age.

Like most audio commentaries, it should probably be avoided until one has watched the film a few times and developed a personal response, but it's a sensitive and informed critical interpretation, and New Yorker deserves kudos for including it.

—D.C.

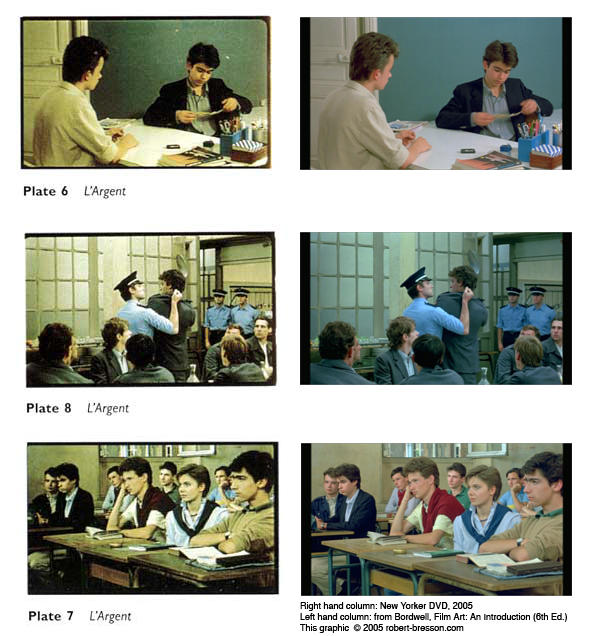

The DVD Transfer The New Yorker DVD cover design is based on Savignac's original L'Argent artwork (very much thanks to New Yorker DVD producer Cindi Rowell, in every respect a true Bressonian). The URL to our article Inside Bresson's L'Argent — An interview with crew-member Jonathan Hourigan is included in the booklet. Also provided is a new essay by Kent Jones, as well as a written appreciation by Olivier Assayas reprinted from the last chapter of the Cinematheque Ontario Bresson Monograph (James Quandt, Ed.). Leonard Maltin, not wanting to be outdone, contributes to Bressonian scholarship 4.5 stars on the DVD cover. The original material provided by MK2, upon which the New Yorker transfer is based, is for the most part of excellent quality. This becomes immediately apparent upon viewing the film as included on the MK2 box set (Region 2/PAL), of which the recent Artificial Eye (also Region 2/PAL) release is a direct port. For more details, refer to the DVDBeaver reviews of the MK2 box set and the Artificial Eye port. We have but one complaint against MK2: MK2 have cropped the film to a noticeable degree. It is hardly disastrous, in this case, but it is a nuisance nevertheless. The following plate is a comparison between actual frame enlargements taken from the film (on the left) and screen grabs from the New Yorker DVD, on the right. The frame enlargements are lifted from the 6th Edition of Bordwell and Thompson's Film Art. This comparison shows that the image is cropped on the right hand side. Bresson's image composition is compromised, as peoples' heads are partly chopped off (as seen in the bottom two image rows, right hand side). This cropping appears, of course, in all subsequent ports of the film (Artificial Eye, New Yorker), and MK2 alone have to accept responsibility for this.

We now focus our attention specifically on New Yorker's DVD presentation of L'Argent. Our main gripe here is that the disc is not based upon a proper NTSC Master. It has been sloppily transferred from PAL to NTSC, resulting in significant ghosting effects. As we have already pointed out numerous times, these kinds of visual deficiencies are totally unnecessary, as equipment is today readily available to properly deal with PAL-to-NTSC issues if one should be forced to use a PAL source in the first place. The following two frame grabs from the New Yorker DVD illustrate the problem.

The first frame exhibits no ghosting, while the immediately following (1/29.97th second later) frame, shown on the right, is clearly a superposition. Click to enlarge frames. We feel sorry for the Bordwells of the future: picking just that one perfect frame for use as an illustration in a book may very well be impossible. The encoding sequence used is, 4 clean frames followed by 2 ghosted frames. (For further reading, see our article Should I buy the PAL or the NTSC version?). Because of its PAL-sourced nature, the film clocks in at a mere 81 minutes instead of the correct 85 minutes. In NTSC-land, this ought not be so.

In conclusion, those in Region 1 who are not yet able to play Region 2/PAL discs, or who find the cost of importing

the MK2 and Artificial Eye discs prohibitive, should definitely spring for the New Yorker disc. Compared to

past New Yorker DVD releases (case in point), it is actually of very good quality – and some love and care obviously went

into its production. Kent Jones' pleasant and unassuming commentary is a real bonus, not found on any other release;

completists and Bressonians on every continent will likely want to get this disc for that reason alone.

—T.T.

|