|

Doug Cummings and Trond Trondsen / robert-bresson.comLancelot of the Lake [ Lancelot du Lac, 1974 ]Region 1 DVD: New Yorker Video, 2004

THE FILM

Lancelot was Bresson's third film in color and many critics feel it is one of his strongest visual works. This is no doubt partly due to the contributions of cinematographer Pasqualino De Santis, who had worked with Luchino Visconti and would continue to lense Bresson's final two films. Its careful chromatic scale of dark reds and browns and glowing torchlight on canvas tents lends the film warm tones that serves as counterpoint to its otherwise severe interpretation of the final days of King Arthur, whose Knights of the Round Table have returned from their Grail quest empty-handed and dispirited. As Kristin Thompson comments in her narrative analysis, The Sheen of Armour, the Winnies of Horses: Sparse Parametric Style in Lancelot du Lac:

Bresson has simply eliminated most of the original events [in La Mort le Roi Artu] . . . while expanding a few elements greatly. Thus most of the first half of the film comes from one summary sentence in La Mort: "Now, though Lancelot had behaved chastely by the counsel of the holy man to whom he had confessed when he was in the quest for the Holy Grail, and though he had apparently renounced Queen Guenevere, as the tale has related before, as soon as he had come to court, not one month passed before he was smitten and inflamed as much as he had ever been at any time, so that he fell back into sin with the queen just as he had done earlier." . . . The elimination or compression of events in an adaptation is common enough, of course. But Bresson eliminates or compresses some things only partially, leaving bits of puzzling information which seem to hint that we have missed something along the way." Elliptical narrative is also a typical Bressonian approach, but it does seems particularly pronounced in Lancelot, perhaps because Bresson assumed the legend of King Arthur was widely known. Bresson also elides much of the heroism, action, violence, and grandiose milieu of the traditional tale, fashioning an epic story as a restricted, modest film, with weary characters fighting to maintain their chivalric ideals despite the pressing desires of their hearts at the end of an age.

Throughout the film, conflicts between charaters hinge on these syntactic interchanges where a word such as faire or vous becomes the pivot of the discourse as it is played on, changed, rhymed, or denied. One could profitably make a list of the many verbs that tie together this discourse, almost always stated in a forceful, matter-of-fact declarative sentence, as a verb in the present tense, or as an infinitive. The narrative moves from verb to verb as these characters in search of a goal seek to resolve their conflicting inclinations. The dialogue is as much of a ritual battleground as the tournament. The words are lanced at each other in rapid succession. Hanlon analyzes the meter within much of the film's dialogue, identifying stressed syllables. And if one might question the validity of such an approach, it should be noted that Bresson explicitly wrote on the subject in Notes on the Cinematographer: "Model. Thrown into the physical action, his voice, starting from even syllables, takes on automatically the inflections and modulations proper to his true nature." And later: "Nothing is durable but what is caught up in rhythms. Bend content to form and sense to rhythms." This emphasis on rhythm propels Lancelot's visual and sound design to such an extent that the experience of watching the film can be virtually hypnotic. Bresson also conceives of the overarching narrative in formal terms. While many of his specific ellipses serve to de-emphasize spectacle (several combat scenes occur offscreen, a jousting tournament is visually represented by the powerful legs of the combatants' horses), Bresson begins and ends the film with startling violence. Suited knights stab and decapitate one another in a dark forest, producing torrents of blood; simultaneously, there is a sense of stylization to their movements in the throes of death, actions with unnatural pauses and stiff poses that lend the suited knights a mechanical, inhuman aura.

"Has God forsaken us?" a despondent Arthur asks in the early scenes of the film, noting the empty chairs of the Round Table. A sense of imminent doom pervades the film and serves as a creeping metaphysical antagonist. "We can forestall fate," Lancelot suggests, "deflect the menace." For damage control, Arthur orders his remaining knights to "perfect yourselves, remain united, forget your quarrels, cultivate friendship," but tensions inevitably remain and allegiances shift in light of Mordred's increasing hostility. Besides Lancelot (Luc Simon), the knight whom Bresson highlights the most is Gauvain (Humbert Balsan). While Lancelot oscillates between his loyalty to Arthur and his love of Guenièvre (Laura Duke Condominas), Gauvain struggles to maintain his idealization of Lancelot and heroic knighthood in general. "[Mordred] is everything that you and I despise," he tells Lancelot. "When he splashed you fording a river you said he offended your horse. How he cringed before you. I dislike weaklings. They should be hanged." Gauvain is perpetually the first person to defend the honor of Lancelot and Guenièvre but his high ideals generate as much conflict as they remedy. Guenièvre's narcissism prevents her from completely accepting these ideals as well. Her exchanges with Lancelot continually elevate their love over the good of the community. When Lancelot asks for her humble consent to free him of his vows to her in order to atone for their love and restore the Round Table, Guenièvre replies, "No, I'll save no one at that price . . . To think yourself responsible for everything is not humility."

"Poor Lancelot," Guenièvre muses, "trying to stand

his ground in a shrinking world." But like Bresson's

concentrated adaptation, which runs less than 90 minutes,

Lancelot's world may be compressed but it retains nobility.

The film is often characterized as a "despairing" film in

Bresson's late oeuvre, but in fact, it's more of an elegiac

lamentation (as opposed to a nostalgic or mythologized

portrait), beautifully rendered in loving, rhythmic care.

–D.C. (May 2004)

THE DVD

The source print used for the main feature exhibits some scratches and dust, but is

in quite good shape. The audio track is perfectly acceptable. The colors are however somewhat

less vivid than what we recall from

seeing the film on the big screen—they are somewhat bland and washed-out, part of

which may be due to the fact that the material is tape-sourced.

There is also hardly any definition in the blacks, or dark scenes.

As also was the case

with New Yorker's A Man Escaped DVD,

the transfer is based upon a PAL master, resulting in 4% speedup (the film clocks in

at a mere 80 minutes) and significant ghosting (see this screenshot).

This is quite unfortunate, especially for the serious student of Bresson. See our A Man Escaped DVD review

for further musings on the topic of sloppy PAL to NTSC conversions. The bitrate is 6 Mbps [plot], and the film comes on a single-layer disc.

Here are six screenshot from the film; click for full-size images.

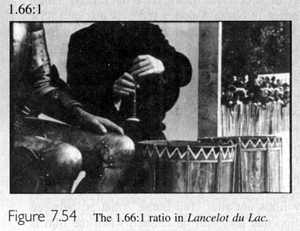

The theatrical trailer included on the disc is not horizontally cropped to the same degree (though it suffers from some vertical cropping). To show how the horizontal cropping seriously alters Bresson's intended image composition, consider the two frames below. On the left is the frame as seen in the main feature of the DVD, and on the right is the corresponding image as extracted from the included non-anamorphic theatrical trailer. Notice the significant change in the framing of the window in the top right portion of the scene.

In conclusion, the fact that this DVD is tape sourced (resulting in ghosting)

and severely cropped (rendering it useless to the serious student of the art of Bresson) certainly

makes it a less attractive purchase. [ Actually, yes, we do feel like screaming right now...!

Restraint! ]. Suffice to say, our more discerning readers may wish to wait for a better release.

Let us hope that the upcoming U.K. release does not suffer from the

same degree of cropping. –T.T. (May 20, 2004)

|